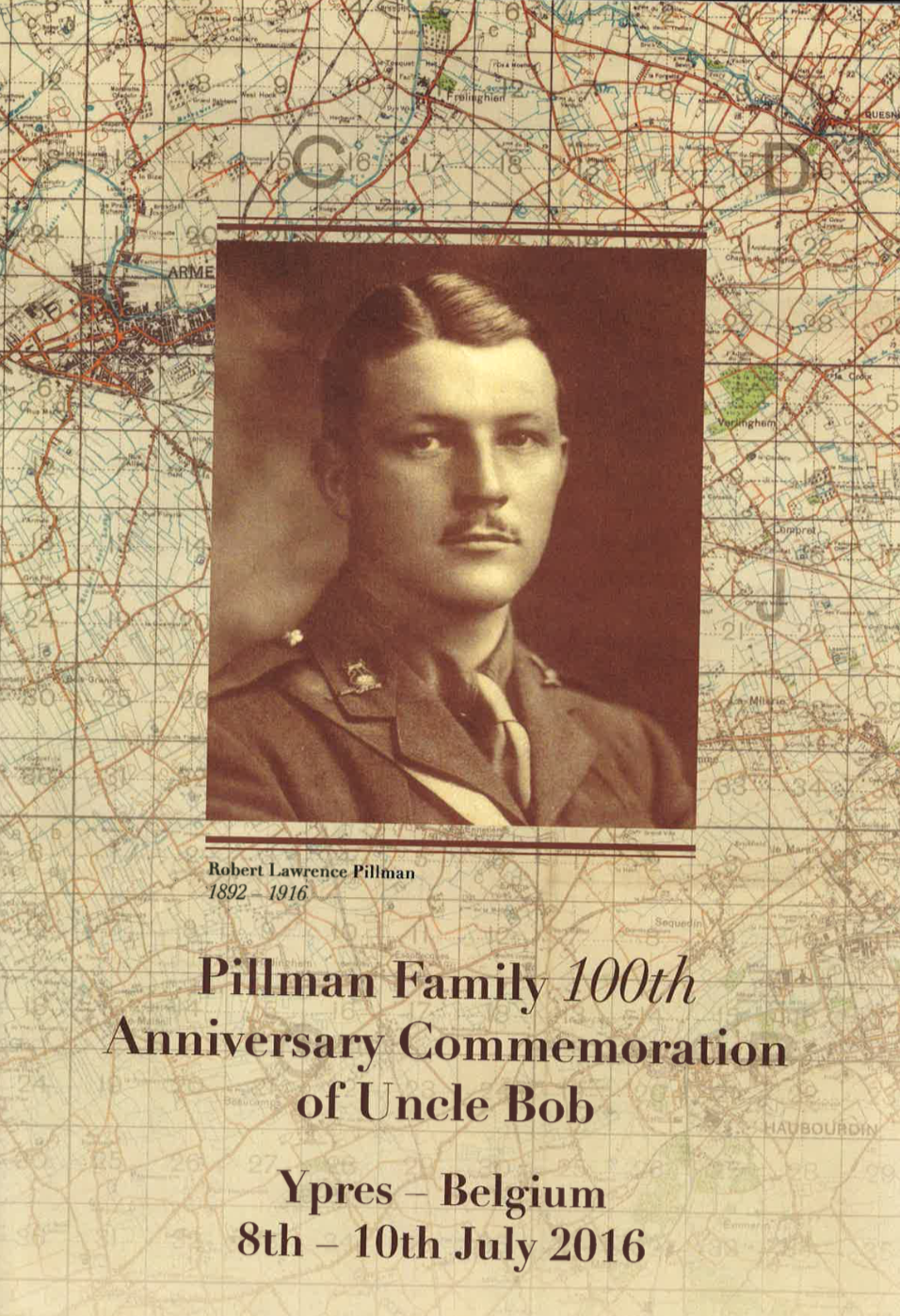

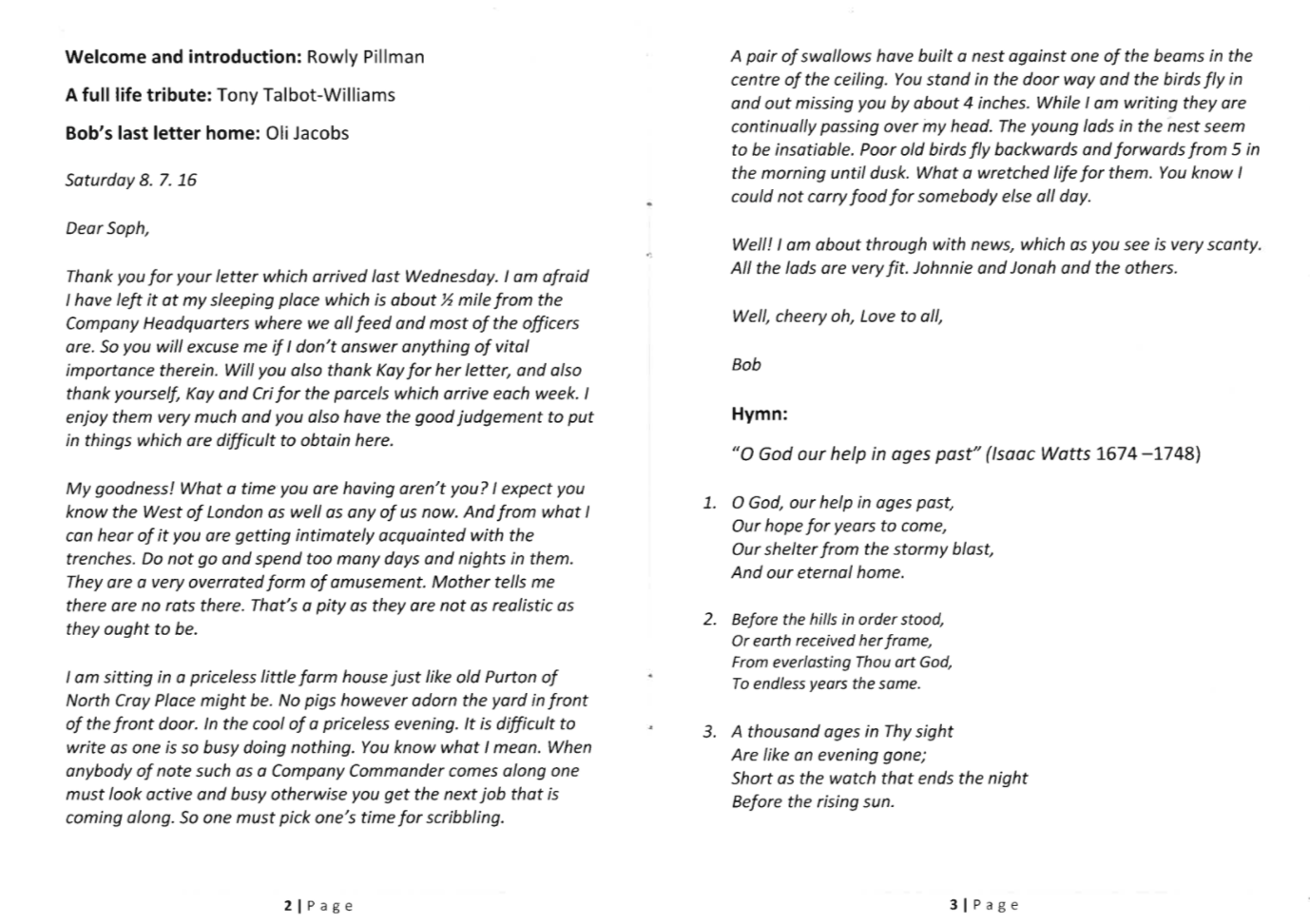

Captain Robert Lawrence Pilman

Dan Hill’s research, edited by Ellie Grigsby

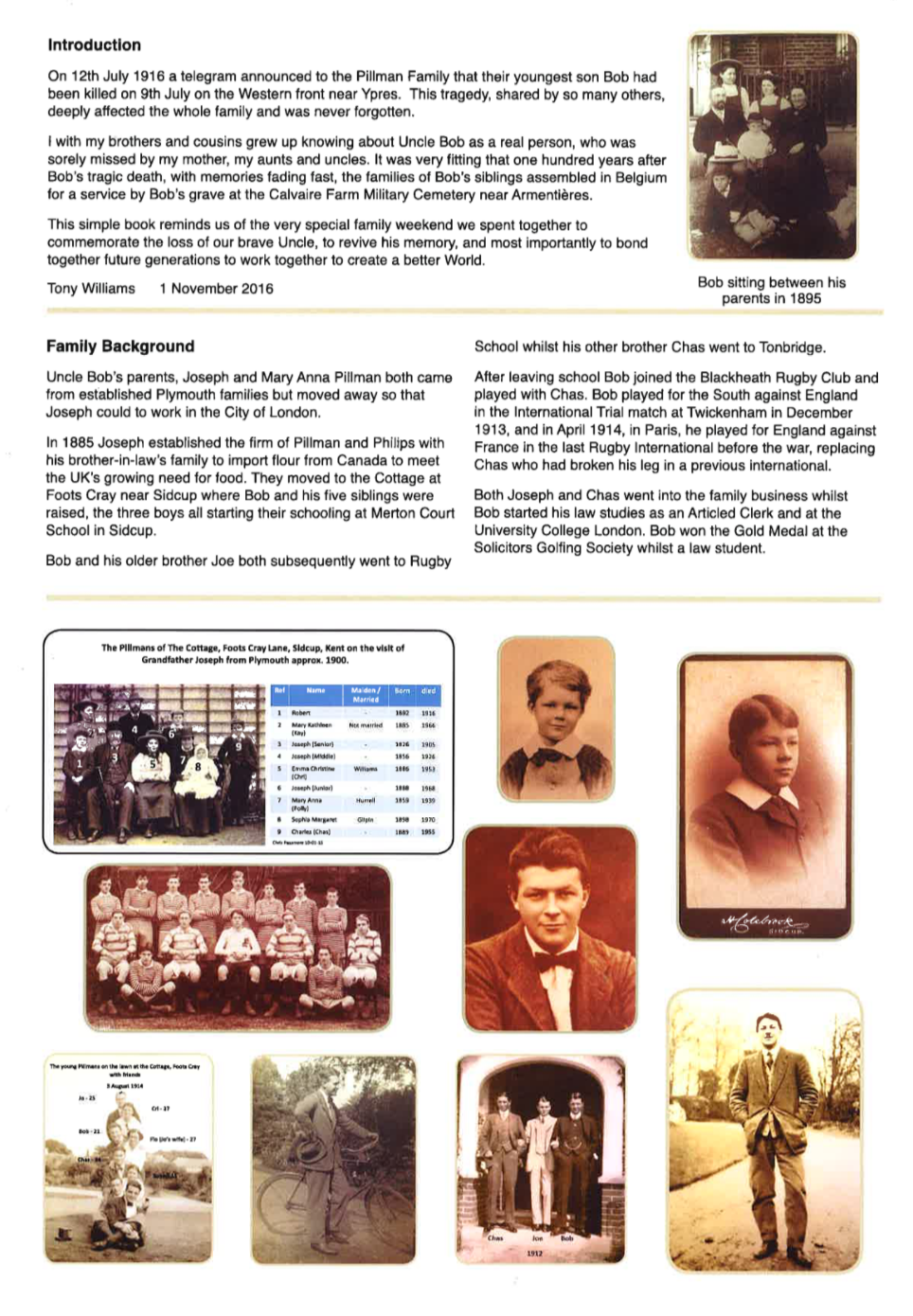

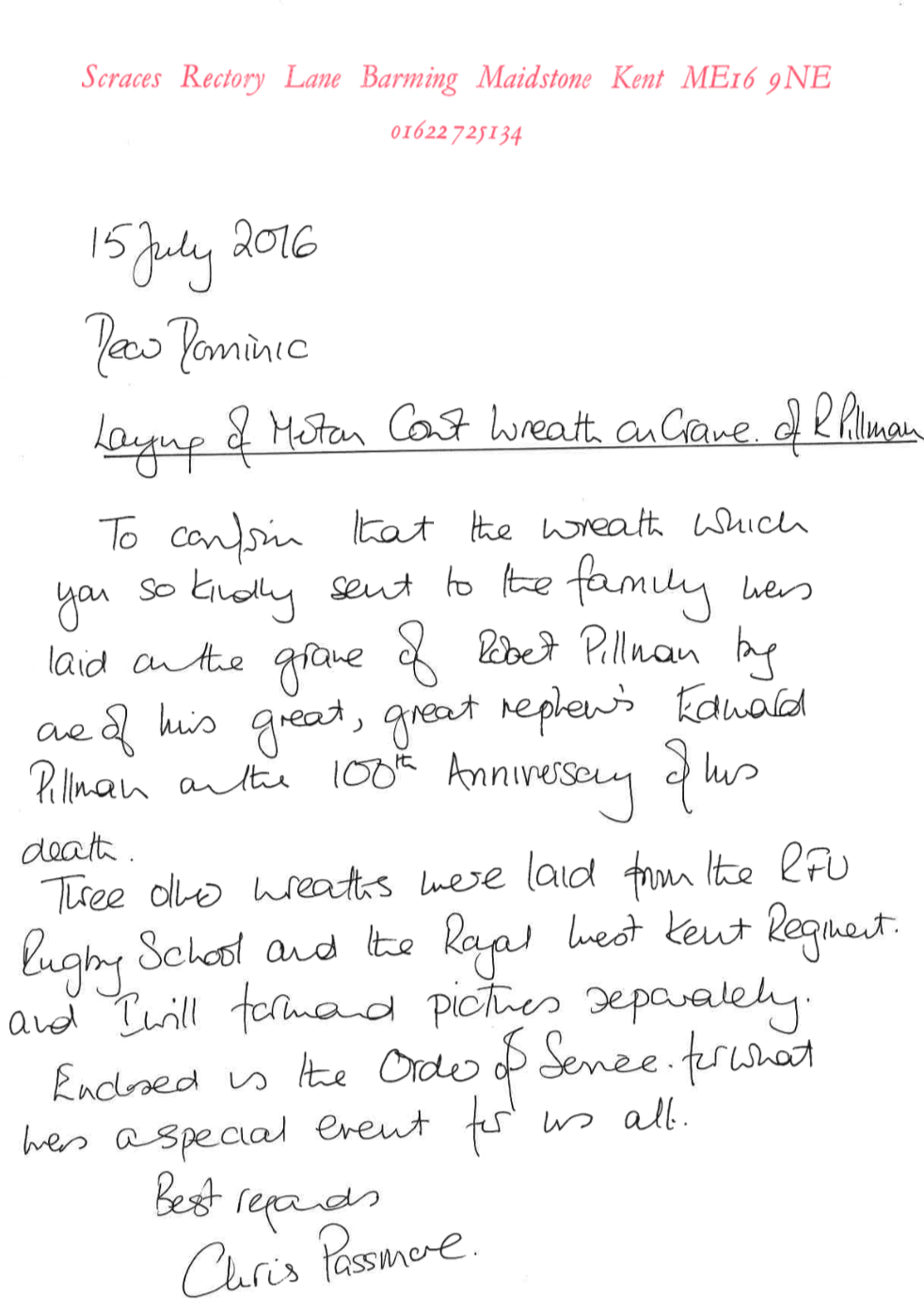

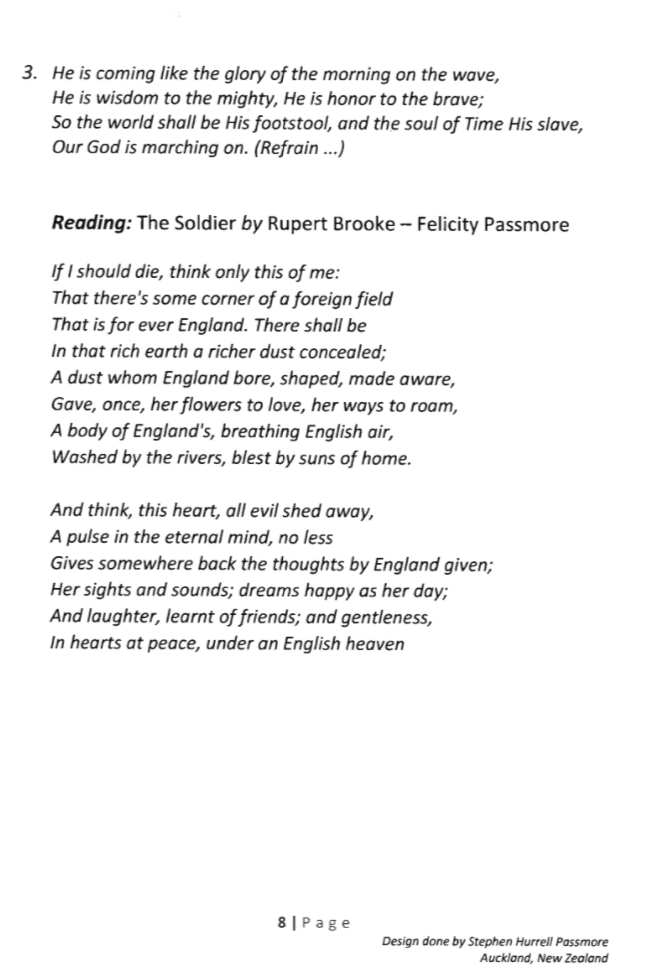

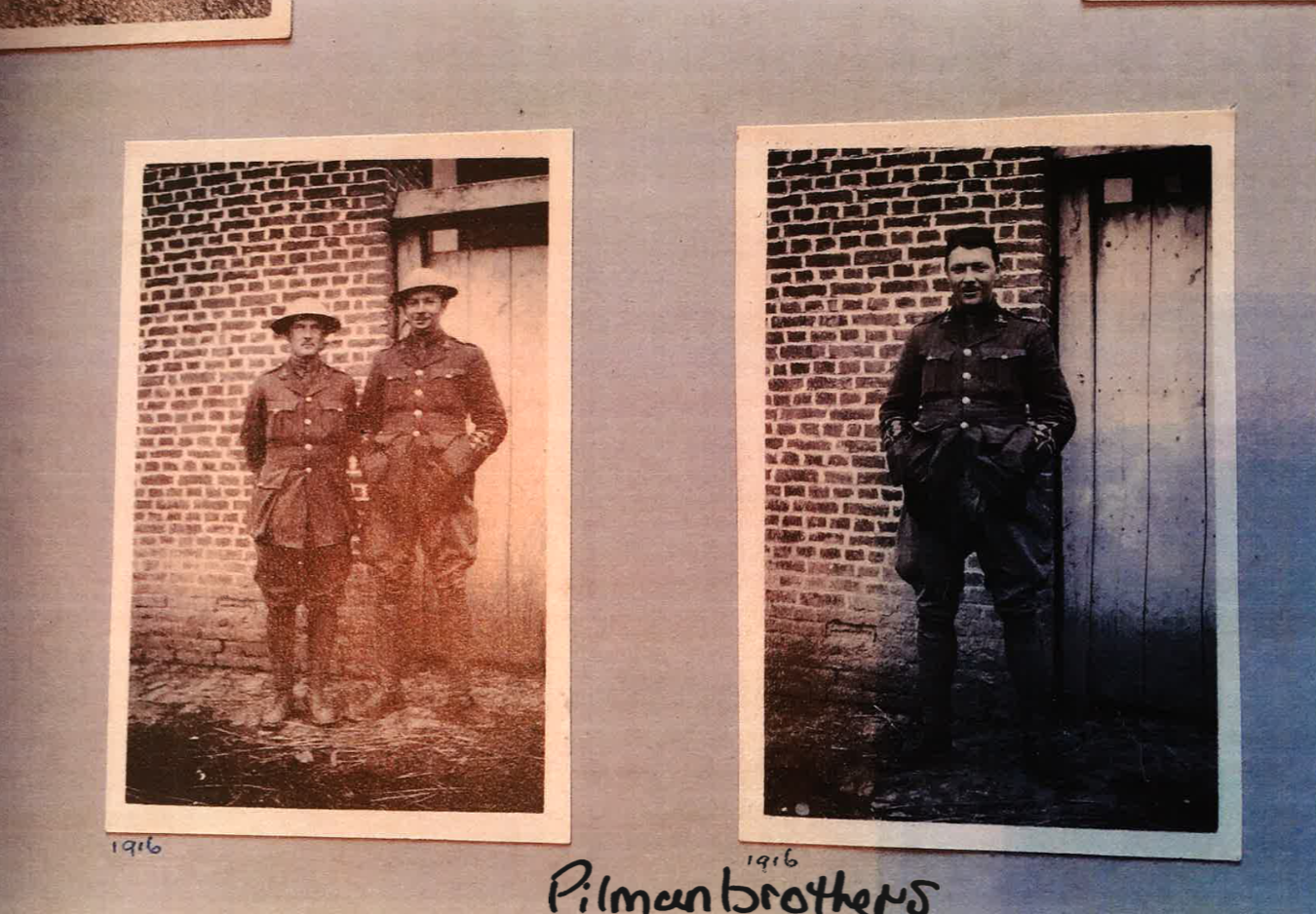

Today’s generation have no tangible connection to the First World War, they may have had a distant relative who served or indeed passed down stories to their grandparents, but memories can fade fast, oral history sometimes cannot survive generational growth. As the centenary since the guns fell silent in 1918 has passed us, and the ‘weeping windows’ and Tower of London installations, strikingly captured our nation’s hearts, symbolically bowing to the milestone mark for historiography, popular culture, academia and family history, we are left fearfully wondering if the people’s connection to the Great War will survive as time cascades on. One family that made an extraordinary effort, to keep alive their ancestor’s story, memory, presence, acknowledgment and education, is the decedents of Captain Robert Lawrence Pilman, known to them simply and affectionately as ‘Bob.’ Upon the 100th anniversary of Pilman’s death, 68 members of the ‘Pilman’ family travelled to Ypres, to unite and be a part of his collective commemoration service by his graveside in Calvaire (Essex) military cemetery. The family read poetry, shared letters exchanged between Pilman and the family whilst serving, recited exerts from the bible, sang hymns, and poignantly listened to two of the younger members of the family, as children, play the ‘last post’ for ‘Bob’ Pilman. A Tony Williams, creator of the ‘Pilman family 100th Anniversary Commemoration of Uncle Bob’ brochure, wrote, he, his mother, aunts, uncles and cousins, ‘grew up knowing about uncle Bob as a real person, who was sorely missed.’ The booklet was designed to ‘remind (the family) of the very special weekend (they) spent together, and most importantly to bond together future generations to work together to create a better world,’ so Williams wrote. On July 12th, 1916, a telegram announced to the Pilman family that their youngest son has been killed on July 9th on the Western Front near Ypres. This heartbreak, shared by so many others, deeply affected the whole family, and evidently, they made a vow to never forget him.

Here is Pilman’s military service story.

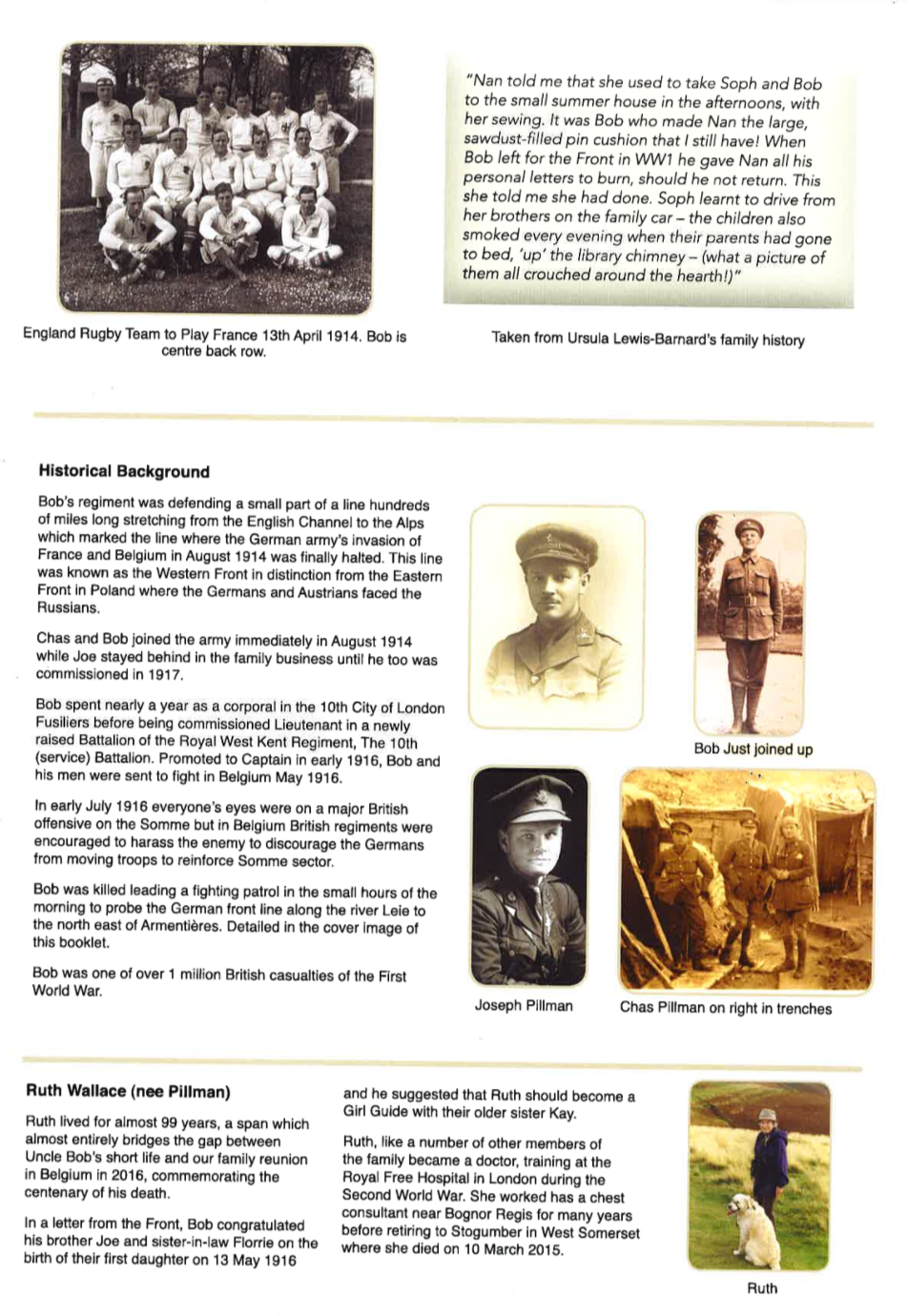

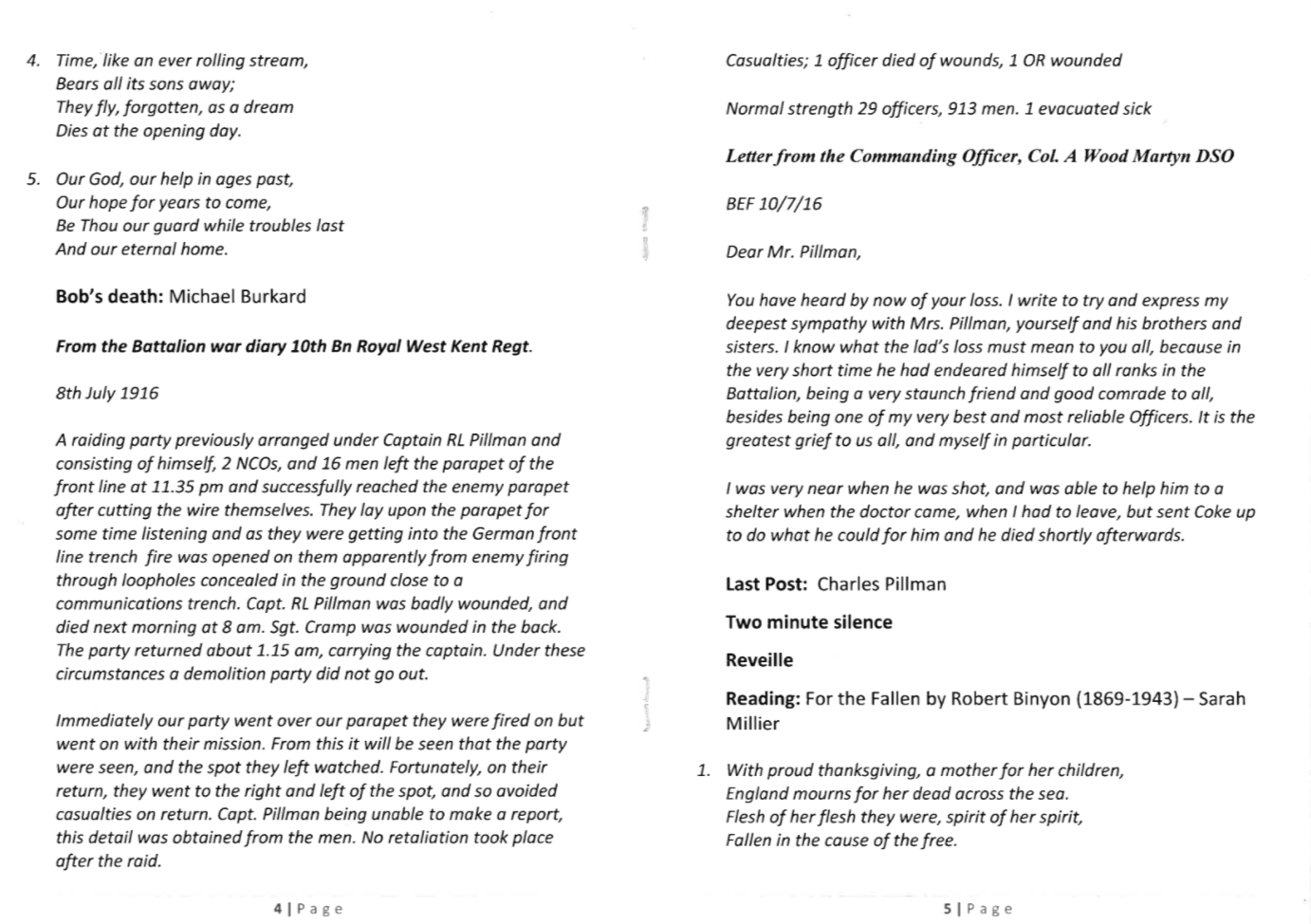

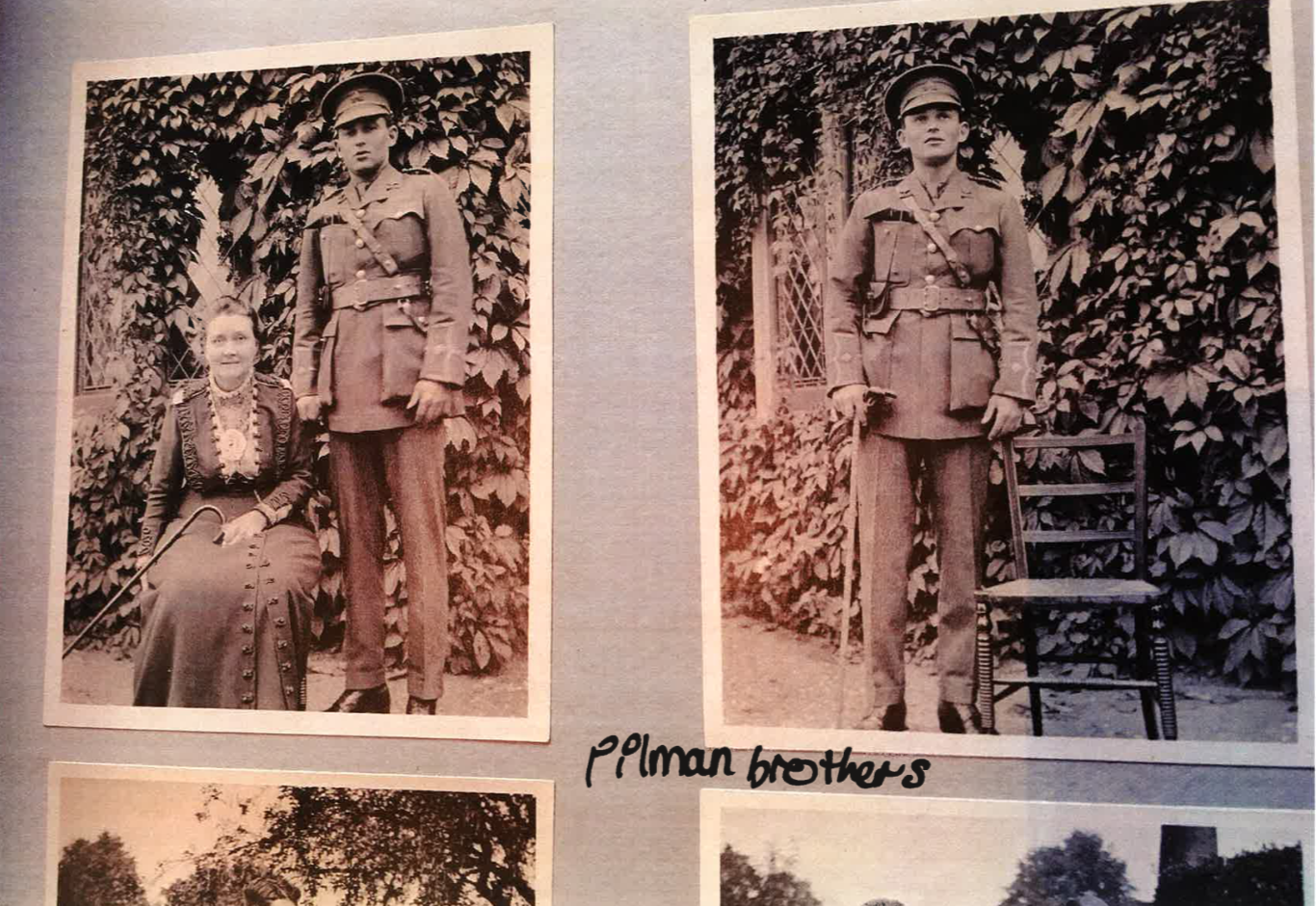

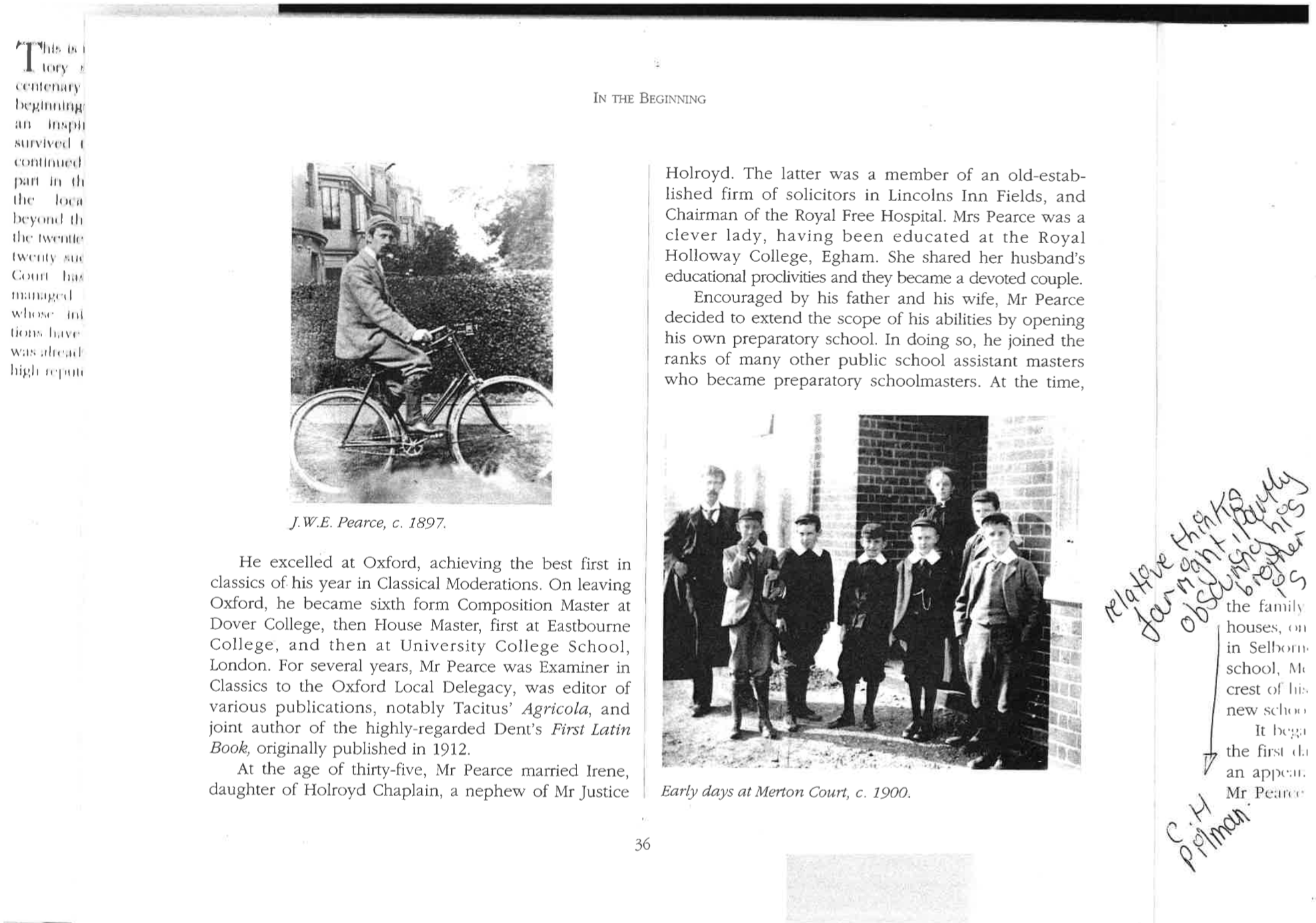

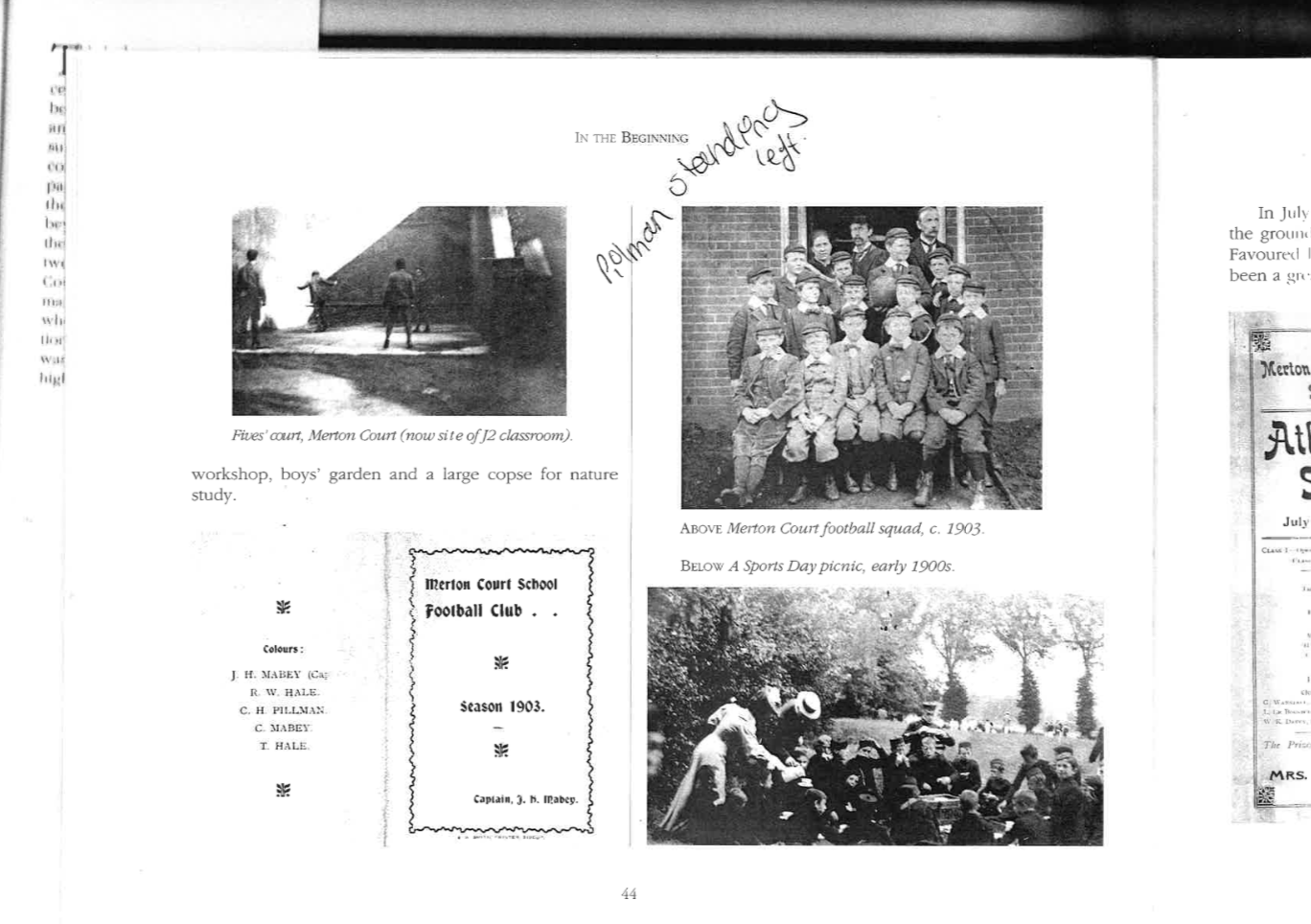

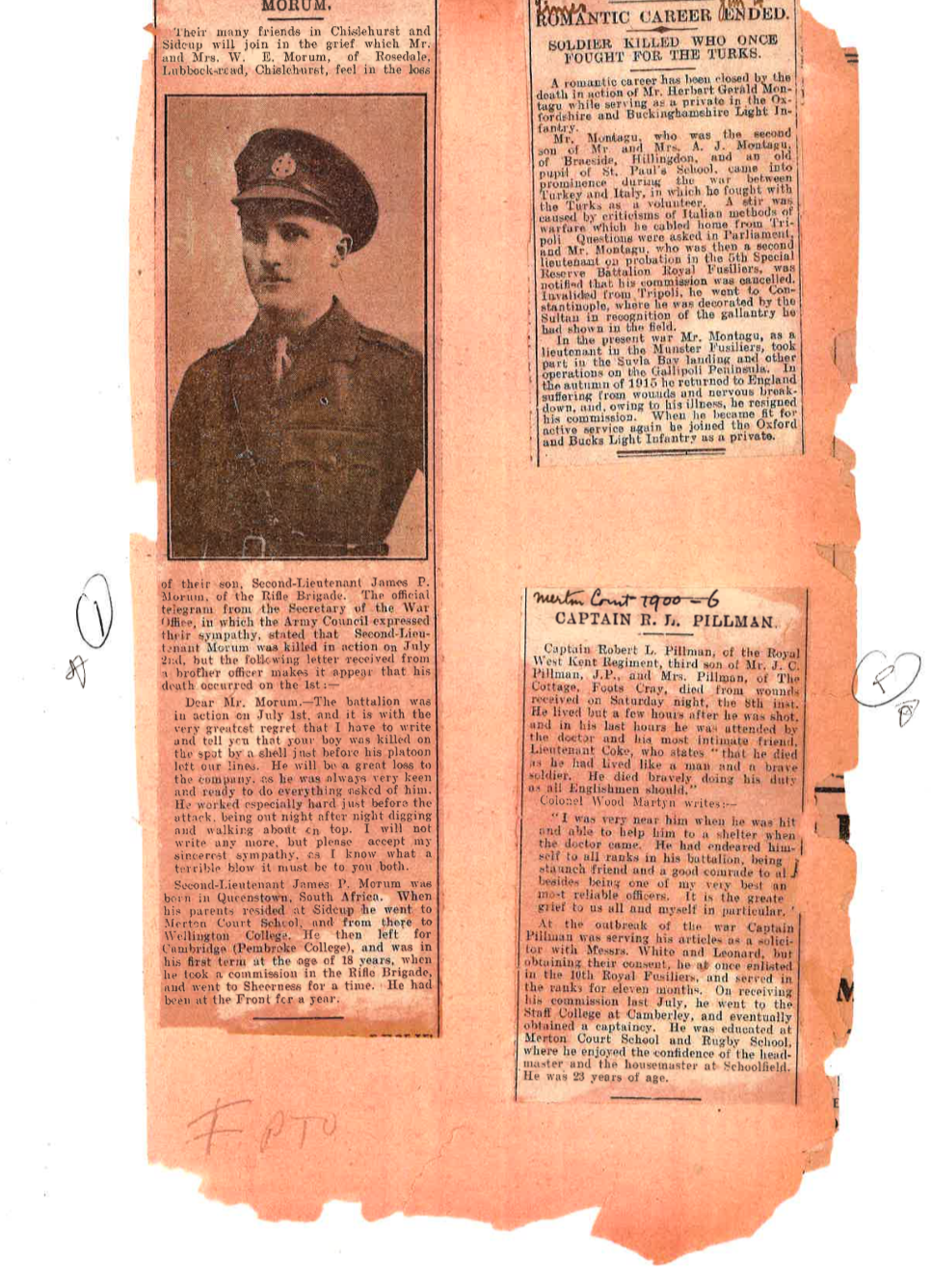

Pilman was born in 1893 in Foots Cray, Sidcup, into an affluent life-style afforded by his father’s occupation. In 1885, Pilman’s father Joseph, established the firm of Pilman and Phillips, with his brother-in-law’s family to import flour from Canada to meet the UK’s growing demand and need for food stuffs. Pilman senior’s more than comfortable salary carried Pilman and his two brothers, Chas and Joseph through private education at Merton Court preparatory school. Using the 1911 National Consensus we find that young Pilman is attending the prestigious Rugby school in Warwickshire. The school roll of honour for its past pupils announces Pilman as a gifted individual; both academically (describing him as ‘quick in thought’) and athletically stating he was ‘remembered as one of Rugby football’s greatest players… which preceded the 1914-1918 war.’ Whilst at Rugby school, Pilman’s flair for the game certainly flourished, as he played for the first fifteen before he left its halls and soon, he followed his brother to the Blackheath club. Besides from Blackheath, Pilman went on to represent Kent. This in turn led to his first major representative match, which was one league higher as he took to the field to play the touring South Africans for London counties on November 16th, 1912 – playing alongside his brother and a host of other star players on the pitch. After graduating from Rugby school, Pilman elected to become a solicitor, being articled to Messrs White and Leonard of Ludgate Circus. In time he would pass the intermediate Law examinations of London University and the Law society. Another great sporting love of Pilman’s, was golf; so it come as no surprise he went on to win the gold medal of the London solicitor’s golfing society. Pilman’s sporting representative career took an upswing once more as he was selected to play for the south of England in the first of the season’s trial matches on December 6th, 1913, at Twickenham and an away fixture held at Stade de Colombes on April 13th, 1914 in Paris. (Pilman replaced his brother Chas who had broken his leg in a previous international); Pilman took part helping to secure the final victory of the season before the world was to alter forever as the dark shadow of war loomed. Pilman’s career was to be abruptly interrupted by the outbreak of The First World War and like so many of that young generation, he was to take up arms for his ‘King and country.’

From viewing Pilman’s medal index card we can see that he had originally enlisted with the Royal Fusiliers (10th battalion) on September 10th, 1914, holding the rank of private, before receiving his promotion to the rank of Lance Corporal, spending nearly a year with them. After completing training with his unit he was selected once again for a commission and became Lieutenant in the (10th battalion) Queens Own Royal West Kent regiment in October of 1915. Pilman was promoted to Captain in early 1916; surviving official documentation omit the exact date of his final commission, but his family state it was ‘early 1916.’ It is evident that this young man was an extraordinarily sharp, capable, and impressive soldier who showed prowess to his superior officers. Pilman arrived in his first theatre of war, on May 4th, 1916, at 11:15am commanding ‘D’ company. After proceeding to march about 4.5 miles south-east of Havre, arriving to their positions around 15:00pm. Unlike most men during this phase of the war, the newly arrived battalion were not heading south to the Somme, but in fact, north to Belgium; here they would be stationed outside the small town of Armentieres to learn the dynamics of surviving trench warfare. Suffering some casualties in Pilman’s first 6 weeks of war, he and his battalion were graced by their first positions being in a somewhat ‘quiet’ sector, but of course, this was not to last.

The evolving nature of trench warfare led to new ways of fighting. No man’s land was the deadly, key ground, it was the transitional space. Especially at night, no man’s land was an incredibly dangerous place to be. Patrols were sent out at night to secretly gather information about their enemy’s defences. These night patrols, were known as ‘trench raids’ aimed with a temporary gain of forced entry into the enemy’s line in order to kill the unbeknownst defenders, destroy or cause as much damage to their fortifications and weapons, and importantly to gain intelligence by capturing maps and other documents to infiltrate their carefully defined strategies of action. Prisoners of war would also be taken if possible; it would often result in gruesome and barbaric face to face fighting, with attackers carrying specialised weapons. Knives, knuckledusters, even improvised ‘clubs’ armed the attacking soldiers; vital for close confined fighting in the trenches to inflict maximum injury upon impact. As the enemies confronted each other, the adrenaline would have been pumping violently through their veins as the scenario was defined by s survival of the fittest motif. There was the huge risk of death, and almost certain enemy retaliation. Men like Pilman really were at the heart of peril whilst on a trench raid.

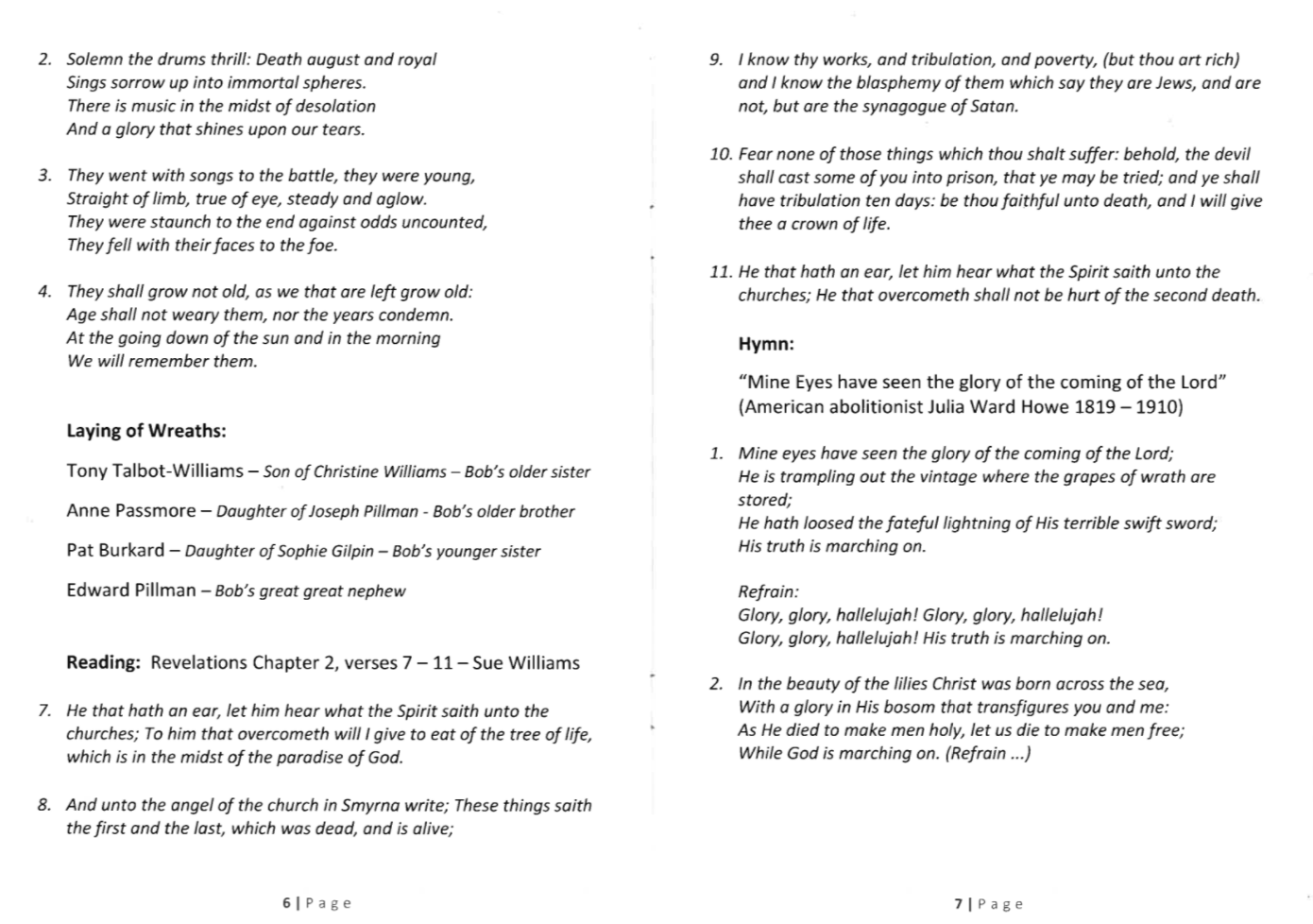

As Pilman would have cautiously clambered over the parapets, no doubt thinking of his boys and wife as his second foot took off from the fire step, he would have dragged himself along the ground, careful to move his elbows consecutively and smoothly to muffle his movement sounds. In camouflaged uniform, Pilman would have kept his head low and no doubt blacked out his face and eyelids to avoid the shimmer of his eyes catching a glimpse from the watchful and alert enemy. The Imperial War Museum informs us that as the war progressed, raids became larger operations, sometimes involving covering parties supporting artillery barrages and even the discharge of poison gas. The ‘secret’ report, written by Brigadier General Davidson (commanding 123rd infantry brigade) relating to the artillery support for the group Pilman led who were due to raid the enemy lines on the evening of Saturday July 8th, 1916 allows us to gather an understanding of their method that night. With secretive work commencing as early as 08:00am that morning in preparation for a raid beginning at 22:00 leading up until past midnight, it reflects how diligently thought out these night raids were and had to be. At 08:00am, commencement of wire cutting signalled the first move. If, the cutting was successful battalion commanders were to report at 12 noon to discuss further progress. It is noted that the ‘wire cutting’ was ‘only being used to mislead the enemy.’ By 22:05pm, artillery and stokes mortars were to fire on enemy front line along the part to be raided and 100 yards on either flank. An artillery barrage was then to formulate leaving 100 yards on either flank of the raid clear and keeping steady fire on the front line beyond these points. By midnight, Pilman’s men were to get over the top of their own parapet and form up just outside their wire in readiness to move. By five minutes past twelve, artillery fire on the enemy’s support line and communication trenches and to the flanks as instructed would signal to the patrol party to move quickly. At the same time, Pilman’s raiding party would advance towards the enemy trenches. It appears the patrol party would have around 20 minutes under the protective artillery and machine gun fire as cover before it ceased, and they would have to draw back. This however was a blue print, a hopeful outlining of the proposed trench raid method. Warfare was unpredictable and so the likelihood of the proposed draft becoming a precise reality was improbable. Using the battalion war diary we can see what really happened during that night raid:

“A raiding party previously arranged under Captain R L Pilman and consisting of himself and two NCO’s and 16 men left the parapet (C.4.A) of the front line at 11:35pm and successfully reached the German parapet after cutting the wire themselves. They lay upon the parapet for some time listening and as they were getting into the German front line trench fire was opened on them apparently through unseen firing through loopholes concealed on the ground close to a communication trench. Captain R L Pilman was badly wounded and died next morning at 8am. Sgt Camo was wounded in the back. The party returned about 1:15am carrying the captain. Under these circumstances a demolition party did not go out.”

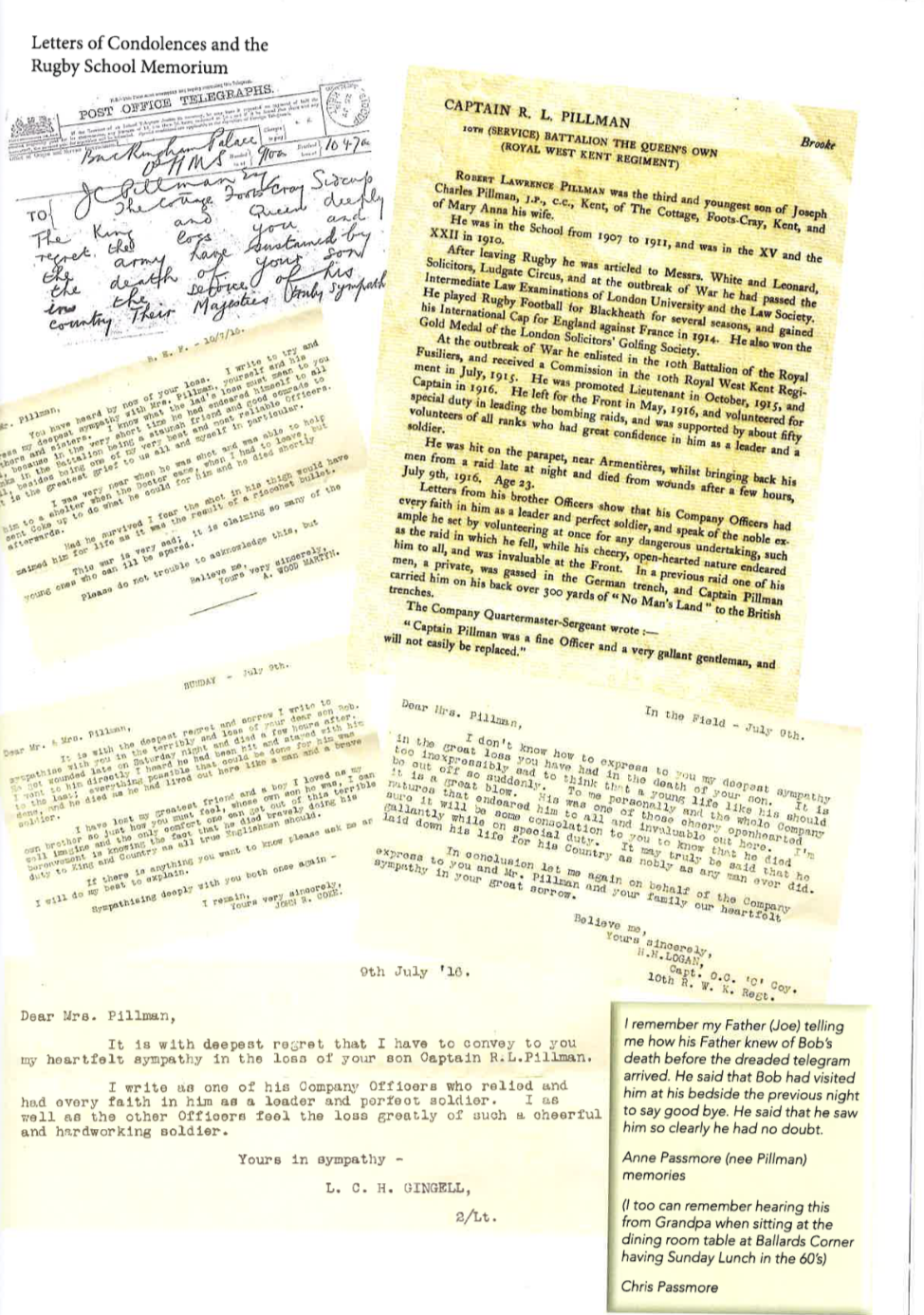

Here we are provided with the vivid imagery of Pilman no doubt crying out in pain as he was scooped up and carried across the battlefield by his urgent men with bated breath, as they leapt over the mounds of dirt and debris blown by artillery fire, against the backdrop of a furious German army as Pilman whimpered each time his limp body was bumped or stretched. Pilman was taken to the regimental aid post but his injuries were so severe he lived but a few (8) hours after he was shot. In his last hours he was attended by the doctor of course, but his closest (Lieutenant Coke) companion sat by his bed-side until he drew his last breath. Coke wrote to Pilman’s parents (upon hearing of his wounding): ‘…I went to him directly I heard he had been hit and stayed with him to the last; everything possible that could be done for him was done and he died as he had lived out here like a man and a brave soldier.’

Pilman left behind a widow and their three sons. Never could they laugh with their father again, cry with him, bond with him, share stories with him, learn from him, or introduce his grandchildren to him for the very first time. The imagination the young Pilman couple no doubt shared, offering each other a fanciful ‘life after the war’ whilst existing in a war-torn world, that could only at that time be dreams, never came true.

Of Mr and Mrs Pilman’s three sons, two died while serving in the 4th Dragoon Guards, the regiment in which their father had won the military cross during the Great War. The eldest, in action on the Normandy beaches; the youngest, accidently in a minefield on the south coast of England just days before D-Day. The other son later died due to ill-health. The Pilman family were victims to the profound impact war held on the way they saw the world, and indeed each other, and to lose three boys to the Second World War, when the Great War was intended as ‘the war that ended all wars,’ it must have felt truly unbearable as, yet another global conflict, rewrote their genealogy.

A family memory shared in the booklet spoke of Pilman asking his mother to burn his personal letters should he not return from the war. Mrs. Pilman had to symbolically and physically destroy her son’s story-telling and listening, as he never came home. She no doubt watched her son’s handwriting crackle and burn into the flames as she stood by and saw his personal effects disintegrate before her; her goodbye not physical, but metaphorical, to her 23-year-old boy.

Tony Williams described the Pilman’s graveside service with his family as, ‘timeless.’

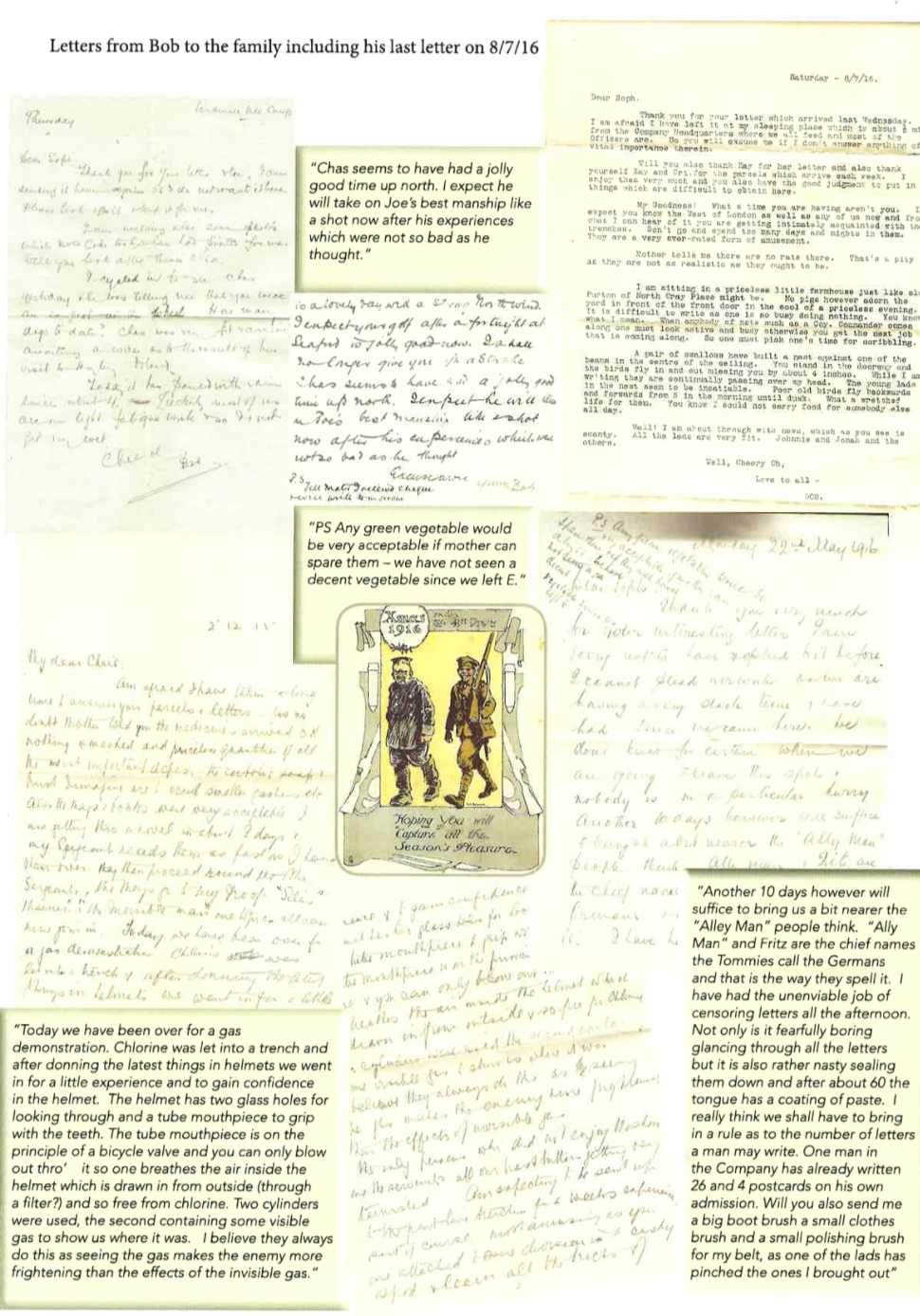

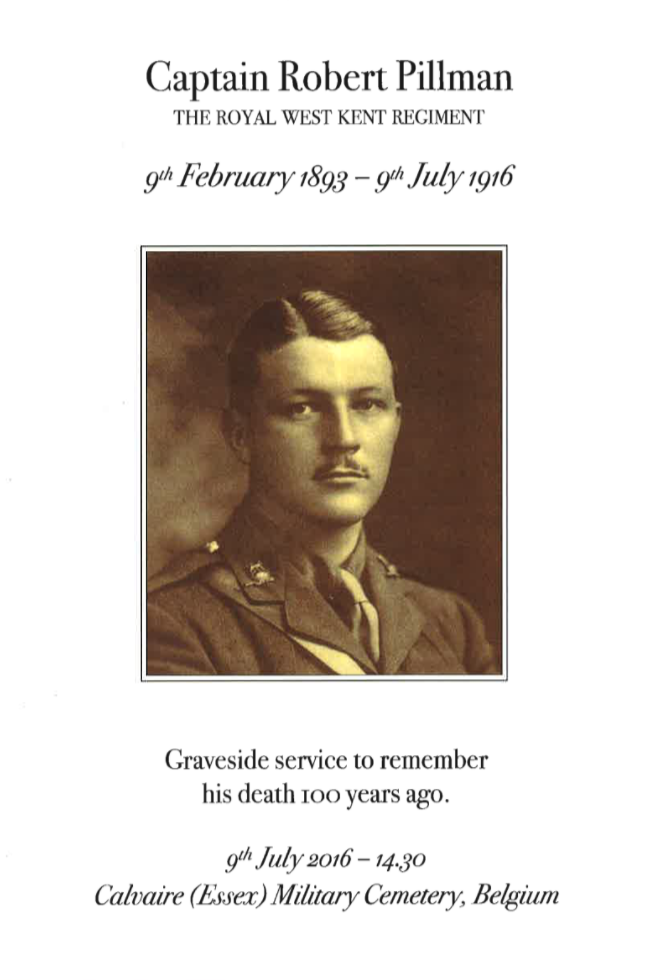

Below is exerts from letters Pilman sent to his loved ones throughout the war and letters of condolences to Mr and Mrs Pilman:

“I am sitting in a priceless little farmhouse just like Old Purton of North Cray place… No pigs however adorn the yard… It is difficult to write as one is so busy doing nothing. You know what I mean. When anybody of note such as a Coy Commander comes along one must look active and busy otherwise you get the next job that is coming along. So one must pick ones time for scribbling.”

“Today we have been over for a gas demonstration. Chlorine gas was let into a trench…we went in for a little experience and to gain confidence in the helmet. The helmet has two glass holes for looking through and a tube mouthpiece to grip with the teeth. The tube mouthpiece is on the principle of a bicycle valve and you can only blow out thro’ it so one breathes the air inside the helmet which is drawn in from outside (through a filter) and so free from chlorine. (Pilman on visible gas): I believe they always do this as seeing the gas makes the enemy more frightening than the effects of the invisible gas.”

“Will you also send me a big boot brush a small clothes brush and a small polishing brush for my belt, as one of the lads has pinched the ones I brought out.”

“I have had the unenviable job of censoring letters all the afternoon. Not only is it fearfully boring glancing through all the letters but is also rather nasty sealing them down and after about 60 the tongue has a coating of paste.”

“It is so inexpressible sad to think that a young life like his should be cut off so suddenly.”

“Believe me, yours sincerely, H.H Logan Captain ‘C’ Coy 10th R.W.K Regiment.”

“I have lost my greatest friend and a boy I loved as my own brother.”

The final quotation is a memory shared by Ann Passmore (Pilman was her uncle, and his father Joseph was her grandfather):

“I remember my father (Joe) telling me how his father knew of Bob’s death before the dreaded telegram arrived. He said that Bob had visited him at his bedside the previous night to say goodbye. He said that he saw so clearly he had no doubt.”